Nigeria, Kenya, Malawi: Portable Diagnostic Devices, Drones and Online Healthcare

African countries are facing healthcare scarcity on every corner, however, with the aid of foreign investments, innovation is progressively addressing these challenges, one step at a time.

This is a monthly newsletter of Faces of Digital Health - a podcast that explores the diversity of healthcare systems and healthcare innovation worldwide. Interviews with policymakers, entrepreneurs, and clinicians provide the listeners with insights into market specifics, go-to-market strategies, barriers to success, characteristics of different healthcare systems, challenges of healthcare systems, and access to healthcare. Find out more on the website.

One of the speakers at the Nextmed Health Conference 2023 said: “In the past, people didn’t age; they just died.” This is still a daily reality in many low-income countries, which lack a workforce, have poor healthcare system structure, and scarce resources.

“My aunt died when I was younger trying to assess healthcare in the country. This is something that everybody in Nigeria has experienced. One or more of their family members have died trying to get healthcare. Even today the president goes out of the country to seek medical care. That's how bad some of the system can be,” describes Ossai Ifeanyi the CEO and Co-founder of CribMD - a digital health consultation platform in Nigeria.

In many cases, healthcare simply isn’t available, but with many problems to solve, innovators are motivated to contribute with their innovative ideas. “There is a lack of equipped and tech-enabled healthcare facilities that are adequate to serve the population in Nigeria. Although this is a problem, it creates an opportunity for innovations within the healthcare field and the potential for partnerships with international organizations that intend to contribute to Nigeria's healthcare system,” says Charles Umeh, Chief Medical Officer of CribMD.

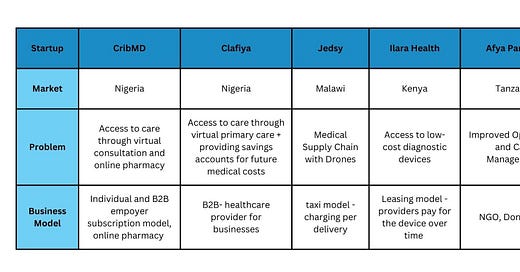

September and October episodes of the Faces of Digital Health podcast presented speakers from four African countries who talked about market conditions, infrastructure challenges, what poor quality of healthcare means in practice, and how they use modern technologies and adaptation to impact healthcare improvement:

But first, let’s look into the healthcare challenges in Africa more closely.

Workforce shortages

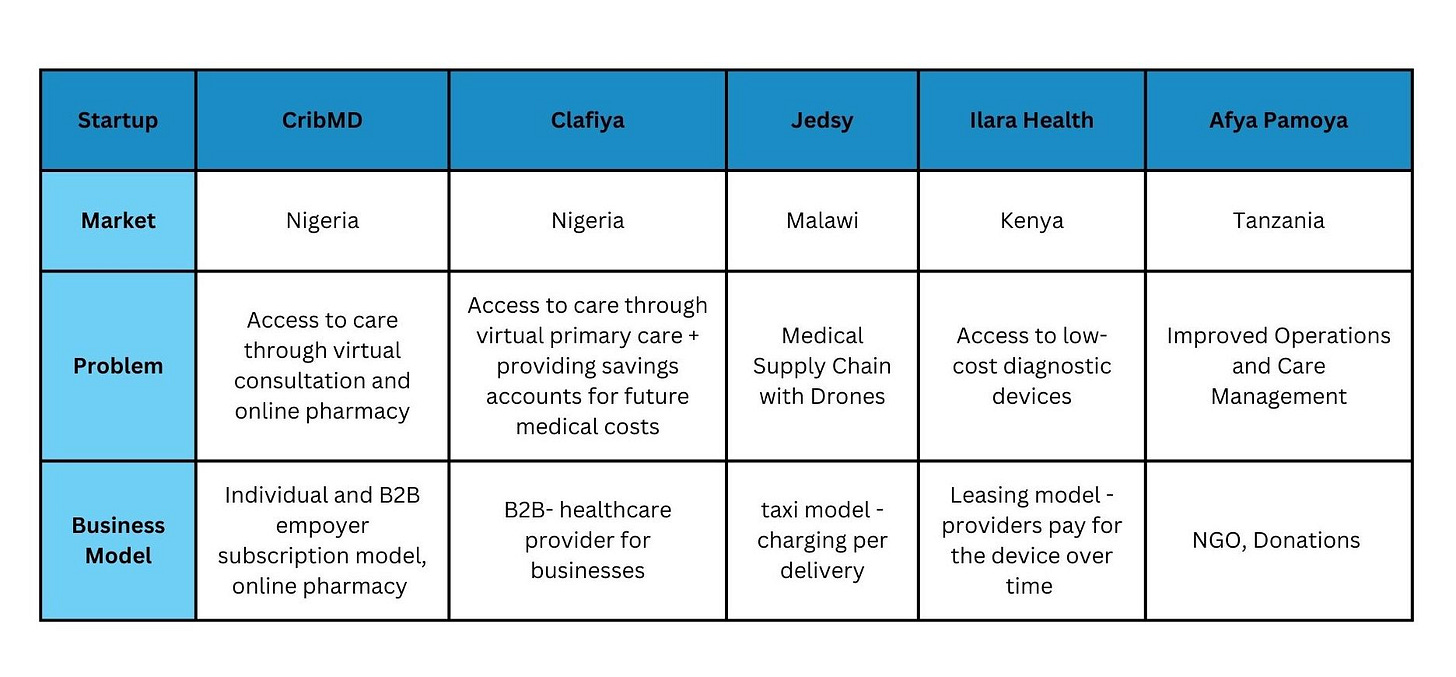

We talk about healthcare workforce shortages on a global level, but in Africa, this term has a significantly different dimension. Nigeria has 220 million people, which is roughly ⅔ of the population of the US. The number of doctors in Nigeria is only between 20-30 000, based on national and international sources. That is 1 doctor per 10,000 people. “It's actually right to say that Nigeria has one of the worst healthcare systems globally,” says Charles Umeh, Chief Medical Officer of CribMD. If we look at other African countries, the situation isn’t much better.

Lack of workforce is not the only factor contributing to poor healthcare. In fact, small practices run by community nurses are common even in rural areas.

In Kenya, there is a shack with a “doctor” or “clinic” sign at every corner, says Emilian Popa, Founder and CEO of Ilara Health. Community nurses working there are equipped to manage basic communicable diseases. “They can identify respiratory and digestive infections and test for basic infectious diseases, but their capabilities largely stop there. Many health issues remain undiagnosed. For example, only one in five people in Kenya who are prediabetic or have diabetes are aware of their condition due to limited testing and understanding of treatment options,” says Emilian Popa.

Khalida Soki is a Consultant Physician and Nephrologist practicing in Nairobi. She moved to Nairobi after working for the NHS. “A lot of people complain about the NHS, but I think nothing could have prepared me for what it was to come home. When I came back, we were about 30 nephrologists in Kenya for a population of 55 million people. The work was overwhelming. While in England, the approach was more multidisciplinary, in Kenya, because of the financial challenges that most people have, you'd find yourself being the sole provider of everything that the patient requires. You are a doctor, clinician, nurse, dietitian, counselor, all in one session,” explains Khalida Soki. The conditions are forcing clinicians to change their mentality from individualized practice to a group. Sometimes they make decision, that are different then they would be in developed countries with more resources. “It's very unfortunate that at some point, you have to decide who you can help and who is best to utilize your time on. Everybody gets dialysis access, but we do, on an individual level, have a conversation with families. Maybe we'd be better palliate this patient because of the utilization of resources.”

Specifically in kidney disease, large families in Kenya can be an advantage, because family members might be suitable organ donors. But this is also changing. “As the sizes of families come down, which is something that's happening now - Kenya's fertility rate is dropping - and as we urbanize, our families get smaller, and people become pocketed into their nuclear families,” says Khalida Soki.

Health Insurance

In 1999, the Nigerian National Health Insurance Scheme was introduced to create Universal healthcare co-coverage, but less than 5% of the population was enrolled in this scheme, according to the International Trade Administration of the US. Payment comes from different sources, explains the CEO of CribMD Ossai Ifeanyi. “Some people pay out of pocket. Some people are paid for by their employers. We have B2B customers whom their employers pay on their behalf. And then we are also working with NHIS and the Ministry of Power and Works. That they pay for their people, right? So they cover some unions.”

Because access to healthcare is complex, and because the healthcare provision is poor, in Nigeria many people don’t see health insurance as an investment or something worth spending money on, says dr. Charles Umeh. And it doesn’t matter if you speak to poor people or people with their own businesses. ”Most of these have money quite alright, but when you approach them to pay for health insurance, they see it as waste. We need to increase the knowledge and change this misconception that health insurance is a waste of money.”

New Technologies and Drones

Africa is sometimes mentioned as a continent with great potential for startups developing more affordable medical devices. In the West, clinical experts complain that these innovations are below the clinical standard. But in an environment where something is better than nothing, these solutions have a great impact. Ilara Health equips a network of small healthcare providers with lifesaving and essential diagnostic tools to improve the quality of medical care in Sub-Saharan Africa. Devices are provided through a loan arrangement where providers receive a device and repay the cost over two years. “Take the example of an ultrasound. In a developed country, a scan at an imaging center might be conducted using a $50,000 ultrasound machine. The portable devices we provide cost only a fraction of that. We offer a lease-to-own model where the clinician pays a monthly fee (let's say $200) over 24 months. At the end of the leasing period, the clinician owns the device,” explains Emilian Popa, CEO of Ilara Health.

Jedsy is a Swiss company developing drones. The company is present in Malawi, where drones transport medicine, spare parts, and anything the health center needs. They are endeavoring to facilitate the transportation of blood bags to health centers, allowing for on-site blood transfusions. This initiative aims to eliminate the current necessity for patients to be transported by ambulance for transfusions. This is a massive barrier because ambulances are not there. “Just to give you an idea, a health center has five ambulances for a million people, and almost every month, they run out of fuel. So basically, the ambulances are working for two weeks a month. Other than that, when people call an ambulance, they have to say, "I'm sorry. We cannot help you,” illustrates Herbert Weirather, CEO of Jedsy. For specific applications, drones present a much more efficient transport option to traditional means of transport. “Logistics and fast logistics are super critical for every single healthcare system in the world. Currently, it's not done in a sustainable way. We are transporting 10-gram blood samples with two-ton cars. That makes no sense. That's why we believe that drone technology will play a major part in the medical industry in the near future,” says Herbert Weirather.

Business Models: The Lack of Infrastructure and Distribution Channel Challenge

When contemplating innovation and sustainable healthcare provision, startups grapple with inadequate infrastructure and a fragmented market. These challenges significantly impede their ability to scale effectively. This is how Jennie Nwokoye, CEO of Clafiya, describes the situation, in comparison to the US:

“When I look at the biggest healthcare companies in the world or the United States, they're able to thrive because they have good distribution channels to access the market. In Nigeria, our healthcare system is very fragmented. Trying to find those distribution channels are a bit difficult. If I look to the United States, I was able to access health care through my employer, either because my parents were employed and I was under their health plan, or when I got off their health plan and had my own health plan, I got it from my employer. Eighty percent of Americans get access to health care through their employer. The other percentage gets it through the government. That means if I had a healthcare startup based in the United States, I would go through health insurance companies to have distribution. If I were a pharmacist in a healthcare startup focused on pharmaceuticals or delivery of medicine, I would be able to visit the big pharmacy chains, such as Walgreens, CVS to have access to the market. In Nigeria, those distribution channels are not there,” explains Jennie Nwokoye.

Clafiya partners with pharmacy companies that also want to provide telemedicine services to their customers or diagnostic companies that want to provide primary health care. In addition, Clafiya is looking into non-traditional channels, such as banks, HR companies, and the food industry, to reach their customer base.

Emilian Popa also believes another mechanism for healthcare provision still needs to be explored, at least for Ilara Health. “It's time to go to corporate, into big factories, big plantations and say, Look, You don't have insurance, you don't insure your low-income employees, or you just give them the national health insurance, which doesn't work in primary care. If your employees are sick, they will miss days of work. How about you pay us a certain amount of money, and we cover those people in our network? So it's very, it's a very different concept of pure insurance, right? And it is just outpatient. We're not touching hospital care because it's a very different world,” says Emilian Popa.

Finding investments and investors

Anyone exploring innovation and technology in Africa quickly realizes that it’s heavily dependant on the capital from outside of Africa. Clafiya and CribMD have founders split between the US and Nigeria. The websites of the two companies and the thinking of the care they wish to provide have a very Western feel. Not being in Africa 100% of the time has its advantages because it makes it easier for startups to find capital from foreign investors but connect to local ones for other types of support, such as connections. The combination is driving progress in Africa.

“I spent most of my life living in the United States; it is an advantage for me to travel to the United States or even to Europe and have access to people who can fund Clafiya. We do have a variety of local investors. Specifically, if I'm speaking for Nigeria, it has had a sharp increase in local investors from the continent since maybe 2015. As a matter of fact, the institutional check came from a local investor. This was very powerful for us because what that meant was that when we started to go on our fundraising journey and pitch to foreign investors, they saw that they had someone on the ground who was backing us. So that means they understand the market, and they trust that we know what we're doing,” says Jennie Nwokoye.

Upskilling the workforce with internet platforms

Building technology and companies is only one piece of the puzzle to improve healthcare. The other one is the upskilling of the existing workforce to optimize care delivery and expand access. Commercial communication platforms are already used for various purposes: CribMD is using Telegram to recruit part-time clinicians, and clinical workers who use Jedsy drones coordinate deliveries through WhatsApp.

Christian Chidoziem is a pharmacy student and entrepreneur who sees LinkedIn or Facebook as a means to improve access to primary care on a broader level. “We have about 8000 pharmacists in Nigeria and all over Nigeria. I think we have more than more than 30,000 community pharmacies. So basically, the community pharmacies are the ones that offer primary healthcare services to the people around their community. But compared to the number of people we have in Nigeria, the number of people offering pharmacy care is very small - like a ratio of one to 6,000 or 6,700. What I am advocating for is a digital pharmacy practice. If we are going to reach a wider audience and for us to give our service at our own base, we need to adopt digital.”

With the heavy use of social media, these platforms are gateways professionals can use to reach patients. “On social media, you, as a pharmacist, can reach a broad audience. You can address 1,000 followers or 2,000 followers on your social media platforms. And you are constantly educating them on health needs and all, promoting your pharmacy to them. That way, they get to know you and reach out to you for whatever care they need,” says Christian Chidoziem.

Before you leave…

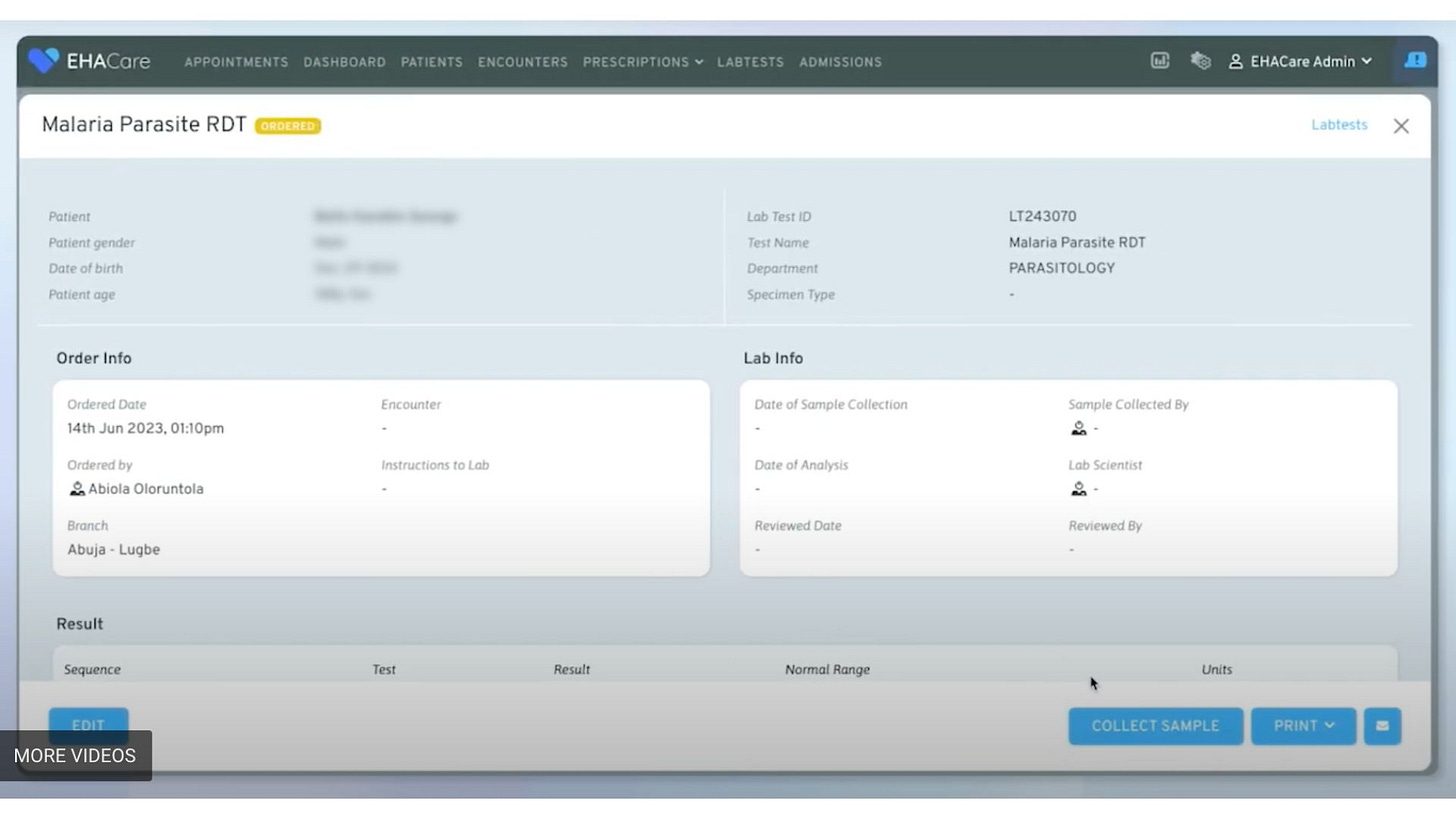

Developing an EHR With Open Standards and Low-Code Tools in 12 months

EHA Clinics, a primary health care service provider in Nigeria, used the Better Digital Health Platform and its' low-code tools to develop EHA Care, an ecosystem of workflow-driven tools to support clinical care, telehealth, home care, community health, continuous quality improvement, and clinical research. They built an EHR with over 80 use cases in only 12 months.